Amelia Earhart was the first woman pilot to attempt and almost succeed in flying around the world at the equator. Her tragic disappearance while flying over the Pacific Ocean triggered a massive search, one of the most expensive in naval history. Over the subsequent years, the mystery of what happened that fateful day in 1937 spawned a multitude of expeditions to search Gardner Island, where it was believed she crashed, as well as hundreds of miles of the ocean floor. All to the tune of millions of dollars and for one reason—to discover the what and where. This is the heart of the mystery. What went wrong, and where is Amelia’s plane? For 87 years, the mystery has been hotly debated. Archived documents about her flight from sources such as Purdue University have been studied, with many experts weighing in with their research, videos, books, and opinions.

In this two-part series, the Mystery Review Crew has delved into the details surrounding her flight and the possible outcomes. Part One focuses on the backdrop of Amelia’s flight from Lae, New Guinea to Howland Island in the Pacific Ocean that tragically went awry. Part Two examines the various theories about the tragic outcome. Is there a last chapter?

The Unsolved Mystery of Amelia Earhart’s Disappearance over the Pacific Ocean

“Every brave life out of the past does not appear to us so brave as it really was, for the forms of terror with which it wrestled are now overthrown.”

– Jean Paul

Amelia Earhart’s Final Confirmed Words

July 2, 1937

This was Amelia Earhart’s last confirmed transmission for her 29,000-mile, record-setting flight around the world at the equator, as recorded in the Coast Guard cutter Itasca’s radio logs.

Amelia Earhart’s disappearance captivated the world. Amelia was an iconic figure in a time when women were barred from many professions in a belief they were incapable of doing a man’s job. A perception that the coming war would change, but Amelia Earhart had already started to break down the barriers. She became a pilot, setting records in a dangerous field in its infancy. Amelia was a leader for women’s rights, opening doors for others to follow. She established the Ninety-Nines, an organization for the advancement of women pilots. Amelia was an author, a public speaker, a marketing entrepreneur with a line of clothes and other products to raise money for her flying, and the list goes on. On July 2, 1937, she disappeared, but the legacy she left has never been forgotten.

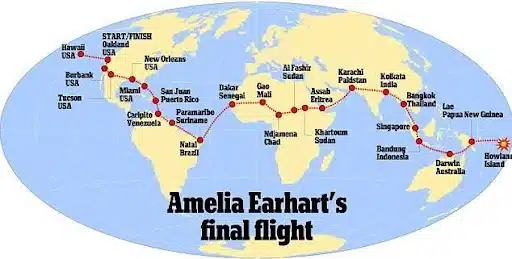

Amelia Earhart’s Final Flight Path

Amelia Earhart was on the final leg of her historic journey around the world when she disappeared. By the time she reached Lae, New Guinea, she had completed approximately 22,000 miles of the flight. Seven thousand miles remained to complete her journey in California with two stops, Howland Island and Hawaii.

At 10 a.m. on July 2, 1937, Amelia Earhart and her navigator, Fred Noonan, departed from Lae, New Guinea. The flight has been termed the “flight into yesterday.” Due to the International Date Line, Amelia left on July 2nd and disappeared nearly twenty-one hours later on July 2nd.

Since the long hop to Hawaii exceeded the fuel capacity of Amelia’s plane, a Lockheed Electra 10E, she had to stop somewhere in the Pacific Ocean to refuel. The federal government had acquired three small islands near the equator. It was ultimately decided to use Howland Island, a tiny speck of land 1.5 miles long, 0.5 miles wide, and 20 feet high, where a runway was built explicitly for her use.

Many, including Amelia, considered the path to Howland Island the most dangerous of all the segments of her journey. Amelia was facing a vast ocean that she would fly over at night with almost no visual landmarks, and her target was a tiny, very tiny speck of land. To find it, she had to rely on Noonan’s celestial navigation and her communications with naval vessels.

The Itasca, a Coast Guard cutter, would wait at the island to provide radio navigation. The USS Ontario was stationed midway between Lae and Howland for additional support. The ships’ navigational ability to help guide Amelia to that speck of land was crucial.

From the onset of planning for the worldwide flight, there were mistakes and miscommunications between the personnel coordinating Amelia’s flight and the military personnel regarding her radio equipment and the frequencies, 3105 kHz at night and 6210 kHz during the day, that she would use. At the time, no one was aware of the dangerous impact of a failure to ensure the naval ships would be able to communicate with Amelia’s plane.

About Amelia Earhart’s Beloved Chariot the plane she took on her last flight

The Lockheed Electra 10E was a new design in aviation. Lockheed didn’t begin building the Electra series until 1934. Ultimately, there were five versions, A-E. The planes were medium-range, 800+ miles, airliners for crews of two and up to ten passengers. Only fifteen 10Es were built. Amelia’s plane wasn’t built until 1936. It was custom-built for Amelia’s trek around the world. Instead of passenger seats, tanks were installed to increase the fuel capacity to 1,100 gallons. A window was installed in the rear of the plane for the navigator.

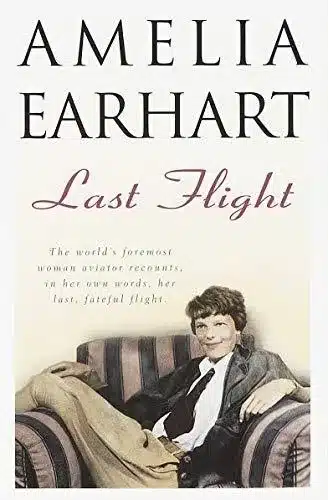

In 1937, her husband, George Putnam, posthumously published Last Flight, a compilation of Amelia’s journal entries, telegrams, and observations during her 22,000-mile trip around the world.

See our review of Last Flight by Amelia Earhart

In Last Flight is a detailed description of the plane’s interior, including the cockpit with two seats, the many instruments, how they were grouped, and their purpose. The Sperry Giro Pilot, a new system, allowed Amelia to put the plane on automatic pilot. She even had a place to keep a few items, such as sandwiches, a thermos, pencils, and a loose-leaf notebook she used to record her thoughts and observations.

A catwalk was installed over the tanks, though she described using a bamboo fishing pole with an office clip to pass messages from the cockpit to the cabin. A window was installed for the navigator’s use. There was a table for the charts. Alongside it were chronometers mounted on rubber to absorb the shock. Other navigational equipment included an altimeter, air-speed and drift indicators, pelorus and compass. As Amelia described in Last Flight, she knew using every available navigational aid was critical as she would be flying over more than 6,500 miles of ocean. It was also why she believed celestial navigation, in addition to the new navigation equipment, was necessary. She described Howland Island as a “fantastically tiny target.”

It was, however, all experimental. Amelia even dubbed the plane “The Laboratory.” How telling. The incomprehensible tragedy is the flight was doomed before she took off from Lae. Mistakes made before Amelia climbed into the cockpit that fateful day, July 2, 1937, would cost her and Fred Noonan their lives.

Amelia Earhart’s Flight

Fuel was a major concern from the start of the planning for Amelia’s record-setting flight around the world at the equator. The logistics for the 29,000-mile trek was a challenging endeavor. In Last Flight, a chart lists the gallons of fuel needed at each location where she would land. If the type of fuel the plane used was unavailable, barrels of fuel were shipped to the location.

Her first attempt started in Oakland on March 17, 1937, for a west-to-east flight. The first leg was to Hawaii, then the second to tiny Howland Island. This attempt ended when she crashed on takeoff from Hawaii.

On March 11, 1937, Kelly Johnson, a Lockheed engineer deeply involved in the design of the Electra, sent Amelia a series of telegrams with recommendations for the operation of the airplane on her flight to Hawaii.

Three hours at 1800 RPM at 4000 feet for 58 gallons per hour.

Three hours at 1700 RPM at 6000 feet for 49 gallons per hour.

Three hours at 1700 RPM at 8000 feet for 43 gallons per hour.

After nine hours fly at 1600 RPM or full throttle at 10,000 feet for 38 gallons per hour.

In a following telegram, Johnson corrected the flight data.

Revised flight data for eight thousand feet at beginning of flight as follows:

Climb at 2050 RPM to 8000 feet

First three hours at 1900 RPM for 60 gallons per hour.

Next three hours at 1800 RPM for 51 gallons per hour.

After six hours use data given in previous letter or wire. Gallons per hour should run little under figures given.

In the same series of telegrams, Johnson wrote: Wire me fuel required for trip to Hawaii on arrival there so I can recheck fuel required for other hop. This was a telling request, considering the next hop was to Howland Island. Johnson’s request certainly indicated a lack of certainty regarding the plane’s performance.

In her second attempt, the flight path was changed to East to West due to changing weather conditions on several legs. This change put the hop to Howland Island near the end of the flight. The distance between Lae and Howland Island on a straight flight path was 2556 miles. Amelia had originally estimated her flight time to Howland Island to be around eighteen and one-half hours. Numerous articles referenced that she had 22 to 26 hours of fuel. Of course, that was under perfect flight conditions, which wasn’t the case.The weather had become a critical factor. Even before she arrived at Lae, Amelia had requested weather forecasts. After her arrival, she delayed the takeoff to Howland Island due to weather conditions over the flight path. The forecasts from Pearl Harbor, as recorded in the Itasca’s radio logs, painted a bleak picture.

June 30th: From Fleet Air Base, Pearl Harbor

FOR EARHART LAE WEATHER LAE AND HOWLAND GENERALLY AVERAGE MOSTLY CLEAR FIRST 600 MILES WIND EAST SOUTHEAST TEN TO FIFTEEN PERIOD HEAVY LOCAL RAIN SQUALLS TO WESTWARD ON ONTARIO DETOUR AROUND AS CENTER DANGEROUS PERIOD PARTLY CLOUDY ONTARIO TO LONGITUDE 175 EAST OCCASIONAL HEAVY SHOWERS WIND EAST 10 PERIOD THENCE TO HOWLAND PARTLY CLOUDY UNLIMITED VISIBILITY WIND EAST SOUTHEAST 15 TO 20 ADVISE CONSULTING LOCAL WEATHER OFFICIALS AS NO REPORTS YOUR VICINITY AVAILABLE HERE

July 1st: From Fleet Air Base, Pearl Harbor

FOR EARHART FORECAST THURSDAY LAE TO ONTARIO PARTLY CLOUDY HEAVY RAIN SQUALLS 250 MILES EAST OF LAE WIND EAST SOUTH EAST TWELVE TO FIFTEEN PERIOD ONTARIO TO LONGITUDE ONE SEVEN FIVE PARTLY CLOUDY CUMULUS CLOUDS ABOUT TEN THOUSAND FEET MOSTLY UNLIMITED WIND EAST NORTHEAST EIGHTEEN PERIOD THENCE TO HOWLAND PARTLY CLOUDY SCATTERED HEAVY SHOWERS WINDS EAST NORTHEAST FIFTEEN PERIOD AVOID TOWERING CUMULUS AND SQUALLS BY DETOURS AS CENTERS FREQUENTLY DANGEROUS

On the day she took off, this was the forecast.

July 2nd:From Fleet Air Base, Pearl Harbor

FOR EARHART LAE ACCURATE FORECAST DIFFICULT ACCOUNT OF LACK OF REPORTS YOUR VICINITY PERIOD CONDITIONS APPEAR GENERALLY AVERAGE OVER ROUTE NO MAJOR STORMS APPARENT PERIOD PARTLY CLOUDY SKIES WITH DANGEROUS LOCAL RAIN SQUALLS ABOUT THREE HUNDRED MILES EAST OF LAE AND SCATTERED HEAVY SHOWERS REMAINDER OF ROUTE PERIOD WINDS EAST SOUTHEAST ABOUT TWENTY FIVE KNOTS TO ONTARIO AND THEN EAST TO NORTHEAST ABOUT TWENTY KNOTS TO HOWLAND.

Amelia never received this forecast before her departure. During the initial stage of the flight, she had arranged a schedule for radio communications with a local radio operator, Harry Balfour, employed by the airport. Amelia would transmit at eighteen minutes past the hour and listen for Lae’s transmission at twenty minutes past the hour. Balfour transmitted the weather report at 10:20, 11:20, and 12:20 local time.

Amelia never acknowledged that she received Balfour’s transmissions. Balfour continued to monitor the radio, receiving the following transmissions.

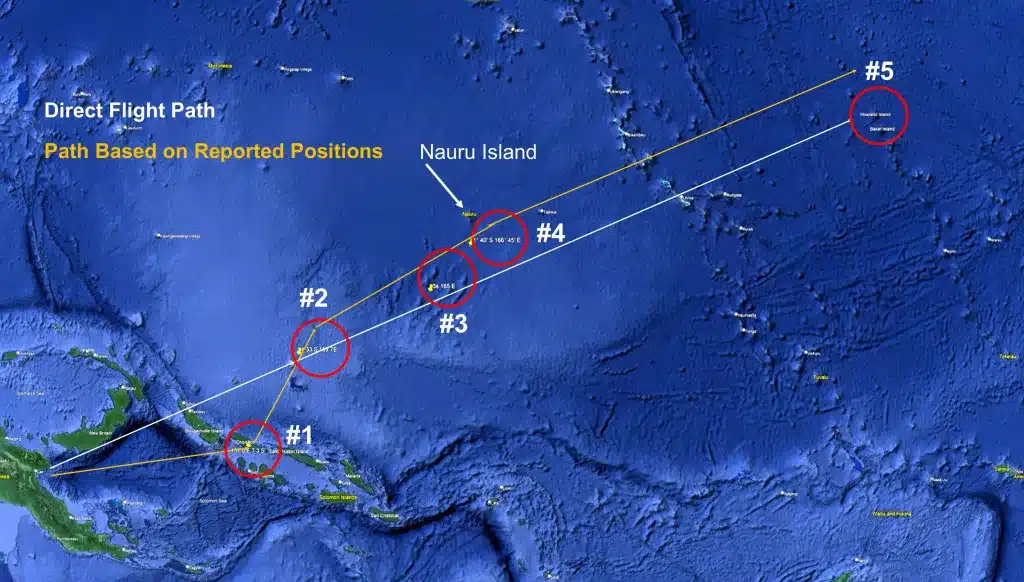

At 2:18 p.m., local Lae time, and four hours and eighteen minutes into the flight, Amelia reported: “Height 7000 feet, speed 140 knots,” “Lae,” “everything OK.” This transmission became a topic of considerable debate as 140 knots is 161 mph. Some experts claimed it was meant to be 140 mph, not knots. 3:19 p.m., local Lae time, Amelia reported: “Height 10,000 feet position 150.7 E 7.3 S cumulus clouds everything OK.” This position heading placed Amelia approximately 250 miles from Lae. Experts have surmised it was incorrectly recorded and should have been 157.0 E 7.3 S, placing Amelia’s plane over Choiseul Island 685 miles from Lae.

(#1) This position is south of the direct line of travel to Howland Island. Had the headwinds and avoiding the “DANGEROUS RAIN SQUALLS” become a factor? At what cost in fuel? The plane’s average speed was 129 mph. Maintaining this speed would add an hour to the ETA (Estimated Time of Arrival) at Howland Island.

5:18 p.m., local Lae time. Seven hours and eighteen minutes after takeoff, Amelia reported: “Position 4.33 S 159.7E height 8000 feet over cumulus clouds wind 23 knots.” This position was northeast of Nukumanu Island. (#2) There was no mention of “everything OK” as she had reported in her earlier messages.

The distance Amelia had traveled could be calculated by plotting the coordinates. She had flown 960 miles (685 to Choiseul and 275 to Nukumanu Island) with an average speed of 132 mph. The deviation added 68 miles. The direct flight from Lae to the reported position northeast of Nukumanu Island was 873 miles. Based on the original estimated speed, 140 mph for the 2556-mile flight, had Amelia not deviated, she should have reached the reported position northeast of Nukumanu in approximately six hours and twenty minutes. She was already an hour behind schedule. In addition, the 68 miles extended the total number of miles to Howland Island to 2624 miles (2556 + 68).

Amelia’s next radio transmission was at 10:30 p.m.: “a ship in sight ahead.” Numerous articles indicated radio personnel on Nauru Island reported they had monitored Amelia’s transmissions. The Nauru personnel believed she was close to the island. The ship she likely saw was not the Ontario (#3) but a freighter, the Myrtlebank (#4), en route from Lae to Nauru Island. The freighter’s reported position was about sixty miles south of Nauru. At this point, Amelia was nearly halfway to Howland Island (#5).

At 0036, Howland time, the Itasca contacted Tutuila Naval Radio asking if the Ontario had heard from Amelia. The Itasca was told no. Yet, this was an hour and a half after Nauru radio had heard Amelia report she had sighted a ship.

According to several articles and videos about Amelia’s flight, it was believed she was already off course and north of her intended flight path as she neared Nauru Island. Fred Noonan navigated by celestial navigation and dead reckoning, using landmarks. At night and over a dark sea with no landmarks, he was limited to celestial navigation. Cloudy skies could have prevented his taking a fix on their position. Amelia told the Itasca it was overcast. Add headwinds, more powerful than she knew, and it was possible Amelia was off course. Extending the flight path would put her north of Howland Island. The deviation to the flight path would add miles, increasing flight time and fuel consumption.

There is also a question about the map Noonan used. Some theorists claimed the map was outdated and Howland Island was in the wrong place. Others have claimed that Noonan had a correct map. Whichever theory is believed, the bottom line puts them off course and north of the island.

Based on her original flight plan, it should have taken Amelia approximately nine hours to reach the halfway point. She was now an hour and a half behind her schedule.

According to the Itasca’s radio log, the first time they heard radio contact from her was at:

- 0245: Heard Earhart plane but unreadable thru static (No response to Itasca’s transmissions). Amelia’s call sign was KHAQQ

- 0345: Heard Earhart on phone (Itasca from Earhart-Itasca from Earhart—overcast-will listen on hour and half on 3105—-will listen on hour and half hour on 3015) The statement “overcast” would indicate there was a problem with Noonan’s ability to get a fix on the plane’s position. He couldn’t see the stars.

- 0455: Earhart broke in on phone-unreadable (No response to Itasca’s transmissions)

- 0614: Wants bearing on 3105 kcs/on hour/will whistle in mic

- 0615: About 200 miles out//apprx//whistling//NW. There was no response to Itasca’s transmissions. Her original ETA should have put her at Howland Island at daybreak. Amelia was still behind schedule, and she didn’t hear the Itasca.

- 0642: KHAQQ came on air with fairly clear signal calling Itasca (voice)

- 0645: Please take bearing on us and report in half hour I will make noise on microphone-about 100 miles out (Earhart signal strength – 4 but on air so briefly bearings impossible. This transmission may have been misinterpreted over the years by assertions she was reporting she was now 100 miles from the island. This wouldn’t be consistent with her earlier transmission of 200 miles. There is another, more valid explanation. Amelia would make noises once she was about 100 miles out. The Itasca was unable to get a lock on her system.

- 0742: KHAQQ calling Itasca we must be on you but cannot see you but gas is running low been unable to reach you by radio we are flying at 1000 feet. According to a second radio log being kept on the Itasca, Earhart stated, running out of gas, only 1/2 hour left. This entry is in the official radio log with a rider it was unverified. It certainly didn’t seem applicable based on the subsequent transmissions from Amelia.

- 0743-46: Itasca to KHAQQ received your message signal strength 5

- 0758: KHAQQ calling Itasca we are circling but cannot hear you go ahead on 7500 either now or on the scheduled time on 1/2 hour (Earhart signal strength 5 on radiophone) (In view of signal strength, it is believed Earhart was closest to Howland at this time)

- 0800-03: KHAQQ calling Itasca we received your signals but unable to get a minimum please take bearing on us and answer 3105 with voice. This transmission was the only time Amelia acknowledged she heard the Itasca. The Itasca radio personnel were never able to lock onto her signal.

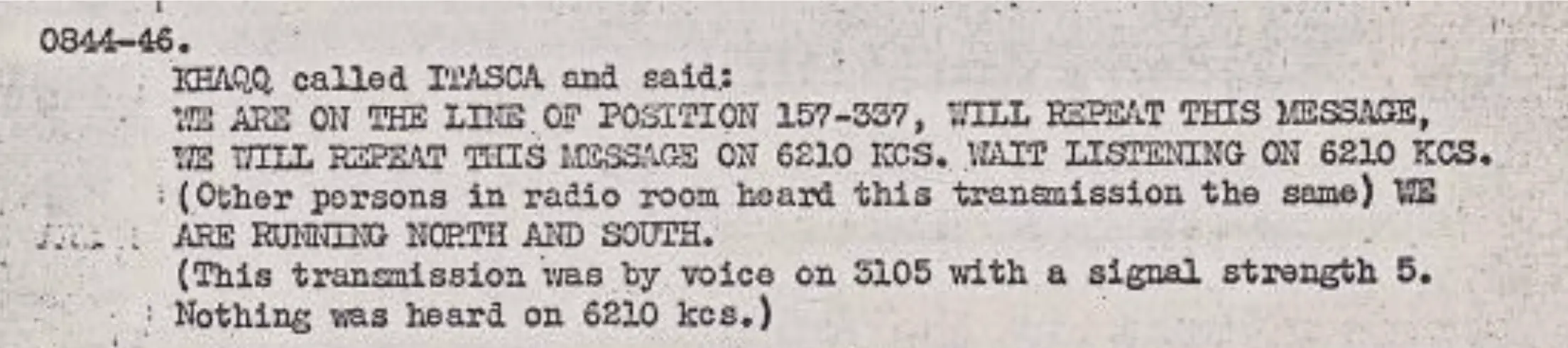

- 0844-46: KHAQQ to Itasca we are on the line of position 157 337 will repeat this message, we will repeat this message on 6210 KCS. Wait listening on 6210 KCS. We are running north and south. (This transmission was by voice on 3105 with a signal strength 5. Nothing heard on 6210 KCS.)

This was the last confirmed transmission from Amelia Earhart for a flight that lasted twenty hours and thirteen minutes.

To be continued in Part Two

Amelia Earhart: Last Flight

The Final Chapter?