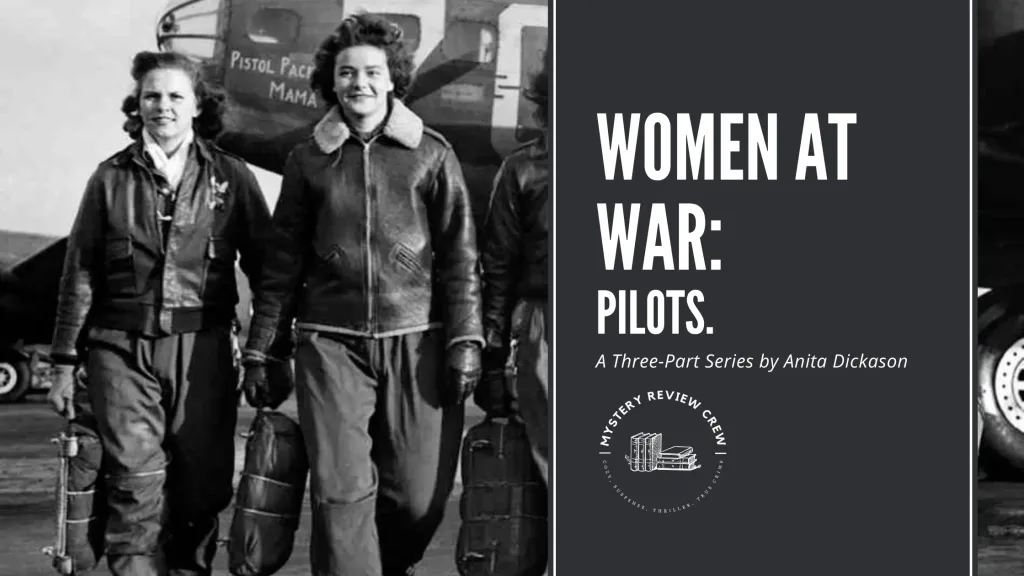

Part Two of Women at War: Pilots (Read Part One Women At War: Espionage) depicts the bravery and courage of women who took on jobs they’d been told they couldn’t do. Women who proved the naysayers wrong. Women who took to the sky and went to war. This is their story.

We are in a war and we need to fight it with all our ability and every weapon possible. Women pilots, in this particular case, are a weapon waiting to be used.

Eleanor Roosevelt, September 1, 1942

*Affiliate links are used in this article. The Mystery Review Crew is an Amazon Affiliate and, as such, earns from qualifying purchases. See our privacy policy and disclosures for more information.

The Women

With the advent of World War II, airpower, controlling the sky, was about to take center stage. The air superiority of the German Luftwaffe that conquered much of Europe and the air attack on Pearl Harbor propelled Allied countries to invest heavily in building their air forces. New technology and new aircraft to fight the battle for the sky emerged. It created a growing demand for personnel—pilots to fly them.

By the 1930s, American women had already broken down the barriers in the aviation field. Blanche Stuart Scott, Bessica Raiche, Harriet Quimby, Willa Brown, Matilde Moisant, Bessie Coleman, Hazel Ying Lee, Edna Garner Whyte, Jackie Cochran, Nancy Harkness Love, and the most notable, Amelia Earhart, were just a few of the women pilots who had already paved the way for what would follow.

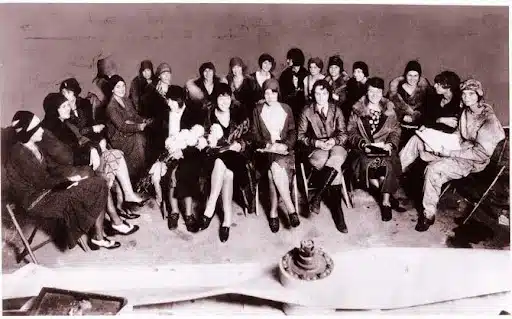

The Ninety-Nines

In 1931, Amelia Earhart was elected as the first president of the Ninety-Nines, an organization for the advancement of women in aviation. The pilots of the Ninety-Nines became an integral part of the war effort. As described on their website:

“Paradoxical as it may be, during the darkest hours of war, some of the brightest pages in the history of women in aviation were written. They ferried the fastest pursuits; flew the giant B-29s. For antiaircraft practice they towed targets, flew searchlights at night, flew simulated strafing missions, laid smoke screens, flew photographic and radio-controlled missions. Some flew engineering test flights while others pushed the cargo-laden carriers around the sky. Many Ninety-Nines taught Army and Navy cadets on Civilian Pilot Training and War Training Service programs through primary, advanced, instrument and stage B cross-country courses, building a great reserve of pilots. In 1944, Ann Baumgartner Carl became the first American woman to fly a jet, the experimental YP-59. They dispelled forever the misconception that great physical strength is mandatory in a pilot.

Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP)

In 1942, in recognition of the need for pilots to ferry aircraft, the Army Air Forces, under the command of General Henry ‘Hap’ Arnold, agreed to use women pilots for flying duties and formed two groups. The Women’s Auxiliary Ferry Squadron (WAFS) enlisted qualified women pilots to transport training aircraft from factories to training bases. Nancy Harkness Love was selected to head the new organization. Love obtained her private pilot’s license when she was 16. After she earned her commercial pilot’s license, she became a test pilot for several aircraft companies. Love tapped into the Ninety-Nines for qualified pilots.

The Women’s Flying Training Detachment (WFTD), under the leadership of Jackie Cochran, would oversee an intensive training program to increase the number of women who could fly for the Ferrying Division. In 1932, Cochran soloed at Roosevelt Flying School on Long Island and received her license after only three weeks of lessons. This was followed with advanced instruction at the Ryan School of Aeronautics, where Cochran earned her instrument rating and commercial and transport pilot licenses. In 1953, Jacqueline Cochran became the first woman to fly faster than the speed of sound. At the time of her death, she held more speed, altitude, and distance records than any male or female pilot in aviation history.

In 1943, General Arnold put Cochran in charge of all the women pilots. Nancy Love was the Executive for women pilots in the Ferrying Command. A month later, the two organizations were merged into a single unit, the Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASP).

Over 25,000 women applied for the program, but only 1830 were accepted. Of those, 1074 graduated from the rigorous training program at Avenger Field in Sweetwater, Texas. These women, combined with Nancy Love’s original pilots, ferried 50% of the combat aircraft within the U.S. during the war, flying over 60 million miles in every type of military aircraft. WASPs flew from 126 bases across the country, towed targets for gunnery training, and served as instrument instructors. They were test pilots, volunteering for the dangerous work of testing new aircraft or planes that had been damaged and repaired.

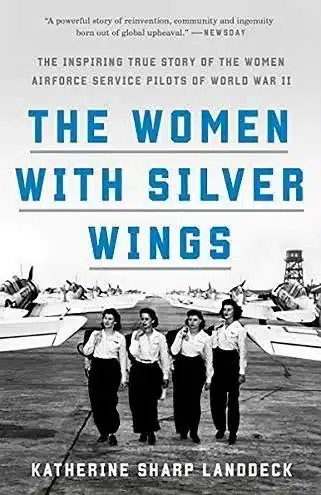

Photo: L to R: Frances Green, Peg Kirchner, Ann Waldner and Blanche Osborne, WASPs who were trained to ferry the Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress, 1944. (Photo Credit: U.S. Air Force / Public Domain)

“In the summer of 1944, U.S. Lieutenant Colonel Paul W. Tibbets had a problem. He was in charge of training pilots on the Army Air Forces’ newest, biggest and most complicated bomber yet, and the task was turning out to be much more onerous than he’d anticipated. Tibbets’ men were putting up unprecedented resistance. In point of fact, the pilots had every reason to be wary. The B-29 was not only much larger and heavier than any bomber the U.S. had flown before, it also hadn’t gone through the years of operational testing to which Boeing had subjected its predecessor the B-17. Initially engine fires were one of the major problems. The planes’ Wright engines were often called the Wrong engines. Part of the trouble could be traced to the engine cowlings that were too tight and often caused fires even before the planes had taken off. Although engine improvements were made over time, fires remained a problem throughout World War II.“— PBS, Women Fly the B-29

(Dorothea Moorman, Colonel Tibbets, Dora Dougherty and Mr Hudson from the FAA)

Tibbets solved his problem by recruiting two WASPs, Dora Dougherty and Dorothea Moorman, to fly the plane. If the women could fly the biggest and the baddest heavy bomber to date, the plane that would ultimately be used to drop a nuclear bomb, then so could the men. For several days, the two WASP pilots, Doughtery and Johnson, ferried the male pilots and their crew chiefs and navigators across New Mexico. Tibbits’ plan worked.

“Colonel Tibbets recalled that, “They did the job. And I don’t know how we could have gotten people to fly B-29 airplanes without them.” Tibbets later served on the Manhattan Project and piloted the B-29 bomber Superfortress “Enola Gay” that dropped the first atomic bomb over Hiroshima in August 1945 at the end of World War II. Without the brave women of WASP, the B-29 Bomber would not have been flown during WWII.” —National Women’s History Museum, Women’s Airforce Service Pilots (WASPS) of WWII

The WASP pilots attended military basic training. They met the military medical standards, completed military flight training, piloted military aircraft, and died in military operations. Yet, they were classified as civilians, not military. As such, they were denied military benefits. WASP pilots paid for their training to acquire a pilot’s license, the cost of transportation to basic training, and their uniforms. Not surprisingly, they were subjected to harassment and discrimination at many of the bases where they served.

Thirty-eight paid the ultimate price. They were killed in the line of duty. Since they were civilians, families and friends paid to have their bodies transported from where they died. They were even denied having an American flag on their coffins.

The WASPs were disbanded on December 20, 1944. General Henry Arnold wrote in his letter of notification to WASP, “When we needed you, you came through and have served most commendably under very difficult circumstances, but now the war situation has changed and the time has come when your volunteer services are no longer needed. The situation is that if you continue in service, you will be replacing instead of releasing our young men. I know the WASP wouldn’t want that. I want you to know that I appreciate your war service and the AAF will miss you…”

It wasn’t until 1977 that the WASPs received their long overdue recognition when they were awarded veterans status and would go on to be awarded the Congressional Gold Medal in 2010.

“Attagirls” of the Air Transport Auxiliary (ATA)

The ATA was formed in 1939 after Great Britain declared war on Germany. As with its American counterpart, ATA was a civilian operation, delivering aircraft from the factories to the RAF and Royal Navy squadrons and supplies. They recruited pilots who were unsuitable for active military duty, either due to age, health, gender, or physical limitations. Hence, the original nickname, “ancient and tattered airmen.” They gained a reputation for being able to take anything to anywhere.

In November 1939, Pauline Gower was tasked with organizing the women’s section of ATA. Gower was a well-known pilot, having amassed over 2,000 hours in the air, ferrying civilian passengers.

Gower initially recruited eight pilots. They were Joan Hughes, Margaret Cunnison, Mona Friedlander, Rosemary Rees, Marion Wilberforce, Margaret Fairweather, Gabrielle Patterson, and Winifred Crossley Fair.

Despite the skepticism over one-eyed, one-armed pilots, the concept of women pilots was met with even more resistance and ridicule. As many of the women pilots came from well-to-do families, they were sometimes referred to as “rich dilettantes” or “Always Terrified Women.”

In the early 1940s, an editor of a prominent monthly aviation magazine wrote, “There are millions of women in the country who could do useful jobs in war. But the trouble is that so many of them insist on wanting to do jobs which they are quite incapable of doing. The menace is the woman who thinks that she ought to be flying in a high-speed bomber when she really has not the intelligence to scrub the floor of a hospital properly, or who wants to nose around as an Air Raid Warden and yet can’t cook her husband’s dinner.”

Despite the prejudice they encountered, the “Attagirls” flew Spitfires and Mustangs and the heavy bombers, Lancaster and the American B17 Flying Fortress. Due to the predominance of the Spitfire fighter plane, the women earned another title, “The Spitfire Girls.” The Spitfire was the most famous plane of World War Two, giving the British a decisive advantage in battling the Luftwaffe.

Jackie Moggridge was the youngest of the “Attagirls.” When she joined in 1940, she was twenty years old. She flew 668 Spitfires.

One of the most formidable of the 166 ATA pilots was Lettice Curtis. In 1937, she gained her private pilot’s license, and a year later, she acquired her commercial pilot’s license. A survey company hired her to take aerial photographs for mapping.

During 62 months of flying, Curtis delivered 222 Halifaxes, 109 Stirlings, Liberators, Lancasters, and other planes. She was the first female pilot to fly the heavy bombers. Altogether, she handed over almost 1,500 aircraft.

She wrote three books about her experiences: Forgotten Pilots (1971), Winged Odyssey (1993), and Lettice Curtis: Her Autobiography (2004).

*Note: Her books appear to be out of print though we’ve found them on Amazon, however, we’d suggest checking local used bookstores for copies.

ATA pilots, men and women, flew approximately 415,000 hours during the war while delivering more than 309,000 aircraft of 147 types, including Spitfires, Hawker Hurricanes, Mosquitoes, Mustangs, Lancaster’s, Halifax’s, Fairy Swordfish, Fairey Barracudas and Fortresses.

Ultimately, 174 pilots, men and women, were killed. Since the pilots were civilians, the airplanes were ferried with unloaded guns or other armaments. However, after encounters with German aircraft in which the ferried aircraft were unable to fight back, the planes were ferried with guns fully loaded.

By the end of the war, 166 women had flown for the ATA, and 11 had received awards for their bravery.

Marina Raskova (1912-1943)

Known as the “Soviet Amelia Earhart,” Raskova was famous for her many long-distance flight records. She became the first woman pilot in the Russian Air Force. Raskova and two other women were awarded the Hero of the Soviet Union medal in 1938. They were the first women to receive the award and the only members of the Soviet Army to accept it before the war started.

In October 1941, Stalin ordered Raskova to form the all-female 122nd Aviation Corps, comprised of three regiments: the 586th Fighter Aviation Regiment, the 125th Guards Bomber Aviation Regiment, and the 46th Taman Guards Night Bomber Aviation Regiment, dubbed the Night Witches. Not only were the pilots women, but so were support staff, mechanics, and engineers. Each regiment had approximately 400 women.

The 586th Fighter pilots flew 4,149 missions, destroying 38 enemy aircraft in 125 battles. The 125th bomber unit flew 1,134 missions, dropping over 980 tons of bombs. It was during a bombing mission that Raskova was killed near Stalingrad in 1943.

46th Taman Guards Night Bomber Aviation Regiment: The Night Witches

One of the most intriguing stories of the bravery of women pilots was the Russian pilots so feared and hated by the Nazis that any German airman who shot one down automatically earned the prestigious Iron Cross medal. These pilots, the Night Witches, flew under the cover of darkness in bare-bones plywood biplanes. They braved bullets and frostbite to bomb German sites.

They were nicknamed the Nachthexen, or “night witches,” by the Germans. The only warning the Germans had was a whooshing sound, like that of a sweeping broom, from their wooden planes as they glided. The small planes didn’t show up on radar. The Germans couldn’t locate them by radio since the pilots didn’t use any radio transmissions. As described in one article, they were “basically ghosts.”

The military provided them with outdated Polikarpov Po-2 biplanes, 1920s crop-dusters used as training planes. These light two-seater, open-cockpit planes were never meant for combat. They were made of plywood with canvas pulled over the top. The aircraft had no protection from the elements. At night, the pilots endured freezing temperatures, wind and frostbite. In the harsh Soviet winters, the planes became so cold that touching them could rip off the skin.

Each plane could only carry one bomb under each wing. Once the bombs were dropped, the pilot returned to their base, reloaded two more bombs and set out on another mission. Each pilot flew multiple missions during the night. The Night Witches dropped more than 23,000 tons of bombs on Nazi targets. They flew more than 30,000 missions. They lost a total of thirty pilots.

White Rose of Stalingrad (1921-1943)

A petite, baby-faced woman became the world’s first female fighter ace. Born in Moscow in 1921, Lydia (or Lilya) Vladimirovna Litvyak began flying when she was fifteen. After receiving her flight instructor license in the late 1930s, she had already trained more than 45 students when Germany invaded Russia in June 1941.

Recruited by Marina Raskova, Litvyak became the first female fighter pilot to shoot down an enemy aircraft and among the first two female fighter pilots to earn the title of fighter ace. Litvyak held the record for a female fighter pilot’s number of kills. According to legend, a white flower was painted on her airplane, hence the label of the White Rose of Stalingrad. Though it should be noted, many disputed this, claiming it was due to Soviet propaganda rather than fact.

In 1943, she was awarded the Order of the Red Star and promoted to Junior Lieutenant. Litvyak was selected to join an elite group of free hunters, where pairs of experienced pilots searched for targets.

During a fourth mission on August 1, 1943, Lutvyak was shot down by German fighters while she was attacking German bombers. A fellow pilot reported seeing her plane streaming smoke as several German Messerschmitts pursued her. It was the last time she was seen. Soviet authorities suspected that the Germans had captured her. Stalin considered being captured as the act of a traitor. She never received the Hero of the Soviet Union medal.

For years after the war, family and friends continued to search for her body. After searching more than 90 crash sites, a site was discovered where an unidentified woman pilot had been buried. The body was exhumed, and authorities concluded the remains were Litvyak. On May 6, 1990, she was awarded the title; Hero of the Soviet Union. Soviet sources credit her with 12 solo kills and four shared over 168 missions.

Still, there are those who don’t believe it was Litvyak that was found in the grave. Some contend she was indeed captured by the Germans and killed. It is a haunting theory reminiscent of another missing pilot, Amelia Earhart. Many individuals believe Amelia was captured and killed by the Japanese.

It was impossible within the short confines of this article to recognize the daring and courage of all the women who conquered the sky to serve their countries. Let these examples stand for all who braved so much.

Many books have been written about their heroism and dedication. Here are just a few of our recommendations if you’d like to learn more: