Is there a final chapter to Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight? After 87 years, are we any closer to finding out why she disappeared over the Pacific Ocean on July 2, 1937? Has her plane been found? What about the fuel? Was she off course? Why couldn’t Amelia hear the Itasca, the Coast Guard cutter waiting at Howland Island to help guide her to the island? Did she crash on an island? So many unanswered questions. Within Part Two, these and more will be examined, including what may be Amelia Earhart’s last flight plan. (You can read part one here)

“Lae, New Guinea, June 30th. After a flight of seven hours and forty-three minutes from Port Darwin, Australia, against headwinds as usual, my Electra now rests on the shores of the Pacific. Beyond the Gulf of Huon the waters stretch into the distance. Somewhere beyond the horizon lies California. Twenty-two thousand miles have been covered so far. There are 7,000 more to go.”

“ Please know I am quite aware of the hazards. I want to do it because I want to do it. Women must try to do things as men have tried. When they fail, their failure must be but a challenge to others.”

—Amelia Earhart.

Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight

Much has been written about the radio equipment on board the aircraft, the breakdown in radio transmissions, Amelia’s competency as a pilot, and Fred Noonan’s navigation. History has not always been kind to Amelia Earhart or Fred Noonan. In many articles, I discovered harsh criticisms of her ability as a pilot and Noonan’s navigational ability. While this Monday morning quarterbacking, an analysis of what went wrong years after the fact, may be necessary during an investigation of an event, it can lead to unfair judgments and opinions. Such judgments are an easy way to fill in the blanks, those gaps of missing details. The type of detail that you had to be there to know what truly happened.

*Affiliate links are used in this article. The Mystery Review Crew is an Amazon Affiliate and, as such, earns from qualifying purchases. See our privacy policy and disclosures for more information.

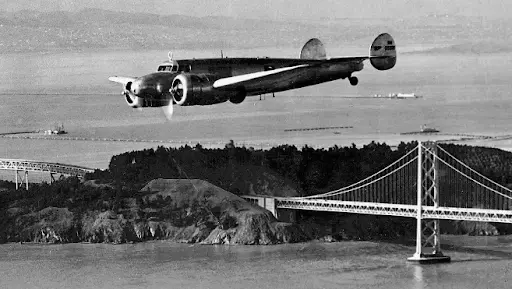

There was a failure to consider the era in which she flew. Amelia learned to fly when pilots navigated by dead reckoning. They flew along roads and railroad tracks, hopping from one landmark to the next. By the 1930s, planes, navigational equipment, and aviation radio communications had just begun to evolve. Lockheed didn’t start building the Electra model until 1934. Amelia’s plane was built in 1936. She acquired the plane through a grant from Purdue University where she planned to teach after her trek around the world. Purdue planned to put the historic plane in a museum.

What I also found noticeably missing was a recognition that for 22,000 miles, Amelia and her navigator successfully overcame equipment malfunctions, airport terrain that seemed to be no better than a rough pasture, and adverse weather conditions.

What was also overlooked was the record Amelia Earhart left us of the events before and during those 22,000 miles of flying around the world. Posthumously published in 1937, Last Flight is a compilation of her journal entries, telegrams, letters, and flight documents she sent home during her record-setting attempt to fly around the world at the equator. Though her journal, her Last Flight, was never finished, what she did leave us is an insight into the difficulties she and her plane encountered. She kept a loose-leaf stenographer’s notebook in the cockpit. Many entries were written while seated in her beloved “chariot.” Last Flight is a wealth of information regarding the 22,000-mile flight, the equipment, the plane, navigation, the maps, and much, much more.

In Last Flight, Amelia described the takeoff from Natal, Brazil. This was the 1,900-mile hop, with a fully loaded plane, across the Atlantic Ocean to West Africa. Their takeoff was scheduled in the early morning hours. The lighted runway was unavailable due to a crosswind. Instead, they had to use a second, grassy runway. To even find it, they had to use flashlights, walking along its path to locate landmarks Amelia could see in the darkness as she guided the plane. They successfully managed to take off. It’s not what I would view as the action of an incompetent pilot.

Amelia also recorded the problems of flying over remote areas with navigational maps that were inaccurate. Wherever she landed, she would pick up tips from other pilots for the routes she’d be flying. Noonan also recorded the difficulties with the maps in a letter he wrote to his wife.

Before Amelia’s first attempt on her record-setting trip around the world, she met with personnel at Pan Am Airways, asking for their help. Pan Am Airways was one of the leaders in the emerging navigational radio technology. Their Clipper airplanes had the latest radio equipment, including direction finders, eliminating the necessity of dead reckoning and celestial navigation. The direction finder could home in on a radio signal to obtain the plane’s position. The company had set up radio stations at Midway Island, Guam, and other locations for ground-to-air radio communications with their pilots. Despite the new navigational equipment, Amelia and Fred would still have to depend on celestial navigation due to the remote areas without the necessary radio equipment along their flight path.

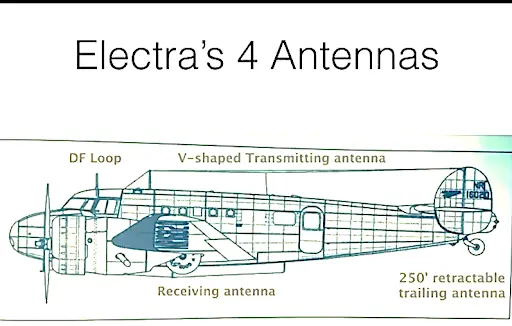

According to multiple reports, Amelia’s Lockheed Electra 10E plane was equipped with four antennas.

- A direction (DF) finder was mounted on the top of the plane above the cockpit.

- A short, v-shaped transmitting antenna was mounted on top of the fuselage. This was described as the antenna used around airports to eliminate the necessity of lowering the trailing antenna.

- A 250-foot trailing antenna on an electrically operated, remote-controlled reel at the rear of the plane. This operated similarly to an anchor. The wire had a weight on the end, which could be lowered or retracted. This antenna also operated on the 500 kHz frequency (VLF) required for the direction finder.

- A receiving antenna was mounted under the belly of the plane. This antenna received radio transmissions on 3105 and 6210 kHz frequencies, which Amelia would use on her flight. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RP5F-7S5yVc

On board for the Honolulu flight in March 1937 were three experienced individuals, Paul Mantz as co-pilot, Captain Harry Manning to operate the new radio system, and Fred Noonan for celestial navigation. During takeoff from Hawaii for the next hop, which was to Howland Island, the plane crashed. Within Last Flight, Amelia described the crash and how it happened. The plane was transported back to California to the Lockheed plant for repairs. It was during these repairs the existing radio system, which had functioned perfectly according to all reports, was removed and replaced with an experimental radio system. Only three had thus far been produced. The V-shaped antenna on top of the fuselage was modified to improve voice transmission on the high frequencies. Several accounts theorized the modification rendered the VLF, 500 kHz, needed to operate the direction finder useless. It may not have been considered important at the time, due to the 250-foot trailing antenna which had the 500 kHz frequency for the direction finder.

For the second attempt, the flight plan was changed. It would be west-to-east instead of an east-to-west crossing. In her book, Last Flight, Amelia cited the reasons were primarily due to changes in the weather over several segments of the flight that were different from the first attempt in March to one in early summer. Amelia also wanted to use the flight from California to Miami as a shakedown cruise for the plane.

For some incomprehensible reason, after she landed in Miami in May 1937, the 250-foot trailing antenna was removed. This decision would have deadly consequences. Fred Noonan was old school and preferred to use celestial navigation. What is recorded in Last Flight might provide the answer. Amelia made numerous comments about Noonan’s ability to pinpoint their locations. Could this have influenced her decision, along with the concerns about fuel consumption and the plane’s weight? In her writings, Amelia never mentioned using the DF equipment during the 22,000 miles she flew before landing at Lae, New Guinea. Noonan was in control of the navigation, and it was dead reckoning and celestial navigation.

This is an excerpt from an article on file at the U.S. Naval Institute:

“MISTAKES AT MIAMI: After deciding to change her route to east-about, in late May 1937 Earhart flew the plane to Miami, where she had the trailing antenna and associated gear removed completely. John Ray, an Eastern Airlines technician who had his own radio shop as a sideline, did the work. Once again, Amelia obviously did not comprehend the devastating impact this would have on her ability to communicate and to use radio navigation. With only the very short fixed antenna remaining, virtually no energy could be radiated on 500 KHz. This not only foreclosed any possibility of contacting ships and marine shore stations but precluded ships—most important, the Itasca—and marine shore-based DF stations from taking radio bearings on the plane, inasmuch as 500 KHz. was the only one of her frequencies that fell within the range of the marine direction finders. Any radio aid in locating Howland Island would have to be in the form of radio bearings taken by the plane on radio signals from the Itasca. Earhart had cut her options severely.”

https://www.usni.org/magazines/naval-history-magazine/1993/december/amelia-didnt-know-radio

Another factor entered the picture. The new era of radio equipment used voice transmission as well as Morse code. Amelia insisted on using voice, not Morse code. Neither she nor Noonan were considered competent morse code operators. The Morse code key had also been removed from the airplane. This became a critical issue when she neared the Itasca. Instead of a series of dots and dashes sent to take a fix on her signal, Amelia planned to whistle into the microphone. The only problem was the Itasca and USS Ontario radio personnel were never informed of Amelia’s radio equipment limitations or that she didn’t use Morse code. The USS Ontario, a coal-burning tug boat, was positioned midway along the route, about 200+ miles southwest of Nauro Island. The ship’s radio personnel were to repeatedly broadcast the letter “N” with the ship’s call sign. The location of the USS Ontario would have provided a critical navigational aid to confirm Noonan’s celestial navigation. Without the 250-foot trailing antenna, there was no way for Amelia to establish communications with the USS Ontario. The Ontario was not equipped with high-frequency radio equipment to hear voice communications.

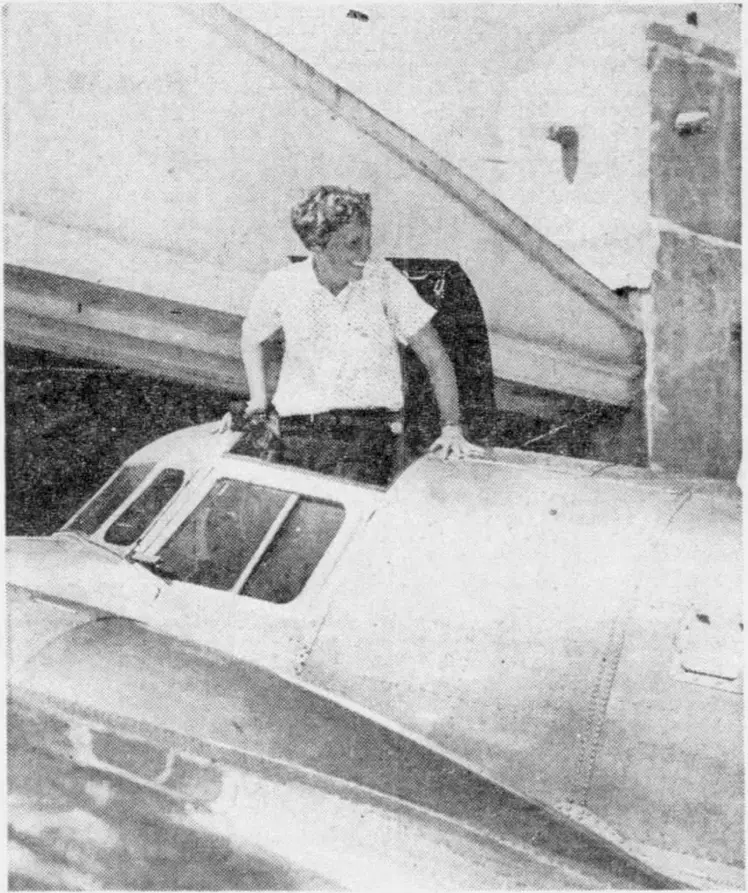

What wasn’t discovered until years later in a video of Amelia taking off from Lae for the flight to Howland Island was that the antenna mounted under the belly of the plane was missing. Photo analyst Jeff Glickman made the discovery when he examined the short video, frame by frame, of Amelia’s plane taking off. As it rolled, there was a puff of smoke near the rear of the plane.

The supposition was that the antenna was ripped off when Amelia taxied over the rough terrain. When the plane started rolling, the antenna mast dragged along the ground. The puff of smoke occurred when the mast and wires were stripped from the plane’s underbelly. Did this damage other components of the plane? It’s certainly a valid question. In Last Flight, Amelia provided a detailed description of the cockpit, even the fact the radio receiver was located under the co-pilot’s seat.

The antenna under the fuselage is clearly visible in this AP photo of Amelia’s plane leaving Oakland for Hawaii in March 1937.

The loss of the antenna meant Amelia could not hear voice transmissions over the short antenna on top of the plane until she was close to the radio signal’s location. If Amelia had known the aircraft was damaged during takeoff, rendering her unable to hear radio transmissions, she would have immediately returned to Lae instead of continuing with the flight. It wouldn’t have been the first time Amelia had to turn back. In Last Flight, an entry describes how she returned to where she had taken off because of malfunctioning navigational instruments.

Amelia didn’t have a reason to suspect a problem with the radio equipment. On June 30th, she tested the radio while on the ground at Lae. On July 1st, she took a test flight to check the radio equipment. She was unable to use the direction finder and believed the reason was that she was too close to Lae.

One of the consistent points in the descriptions in numerous articles of the first half of the flight was that Amelia never responded to the weather updates from Harry Balfour, the radio operator at Lae. An indicator she didn’t hear them. The radio messages she transmitted didn’t indicate that she expected a response from Balfour. Amelia likely had no reason to suspect she had a problem.

So, when did she discover she had a problem? Was it during the night as she flew over that vast, dark Pacific Ocean? The USS Ontario, positioned about halfway between Lae and Howland Island, was southwest of Nauru Island. I never found any reference to her attempting to contact the USS Ontario in multiple accounts of what radio personnel at Nauru Island heard. The USS Ontario informed the Itasca, shortly after midnight Howland time, that they had no contact with Amelia’s plane.

It is likely Amelia didn’t know she had a problem until she needed Itasca’s help to guide her to the island. She expected them to answer but couldn’t hear the ship’s response. She wouldn’t have known the reason. Amelia expected the direction finder would work. She repeatedly attempted to contact the Itasca by making noise on the microphone

- 0614: Wants bearing on 3105 kcs/on hour/will whistle in mic

- 0615: About 200 miles out//apprx//whistling//NW.

- 0645: Please take bearing on us and report in half hour I will make noise on microphone-about 100 miles out (Earhart signal strength – 4 but on air so briefly bearings impossible.

- 0742: KHAQQ calling Itasca we must be on you but cannot see you but gas is running low been unable to reach you by radio we are flying at 1000 feet.

There was only one transmission where Amelia acknowledged she heard the Itasca.

- 0800-03: KHAQQ calling Itasca we received your signals but unable to get a minimum please take bearing on us and answer 3105 with voice.

This next-to-last transmission from Amelia likely occurred when the plane was near the Itasca. She was close enough to hear the radio signal through the short, v-shaped antenna on the top of the fuselage.

Leo G. Bellarts, Chief Radioman on the Itasca, would later write that Amelia’s voice was so loud in the radio room that he rushed on deck, expecting to see her plane.

At 0844-46, she sent her last message KHAQQ to Itasca we are on the line of position 157 337 will repeat this message, we will repeat this message on 6210 KCS. Wait listening on 6210 KCS. We are running north and south. (This transmission was by voice on 3105 with a signal strength 5. Nothing heard on 6210 KCS.) She was gone.

During the massive search that ensued, numerous reports started to surface from radio operators claiming they heard Amelia on the radio asking for help. While many were debunked, a few added legitimacy to the assertion that she managed to land on another island. These transmissions gave rise to one of the primary theories of what happened.

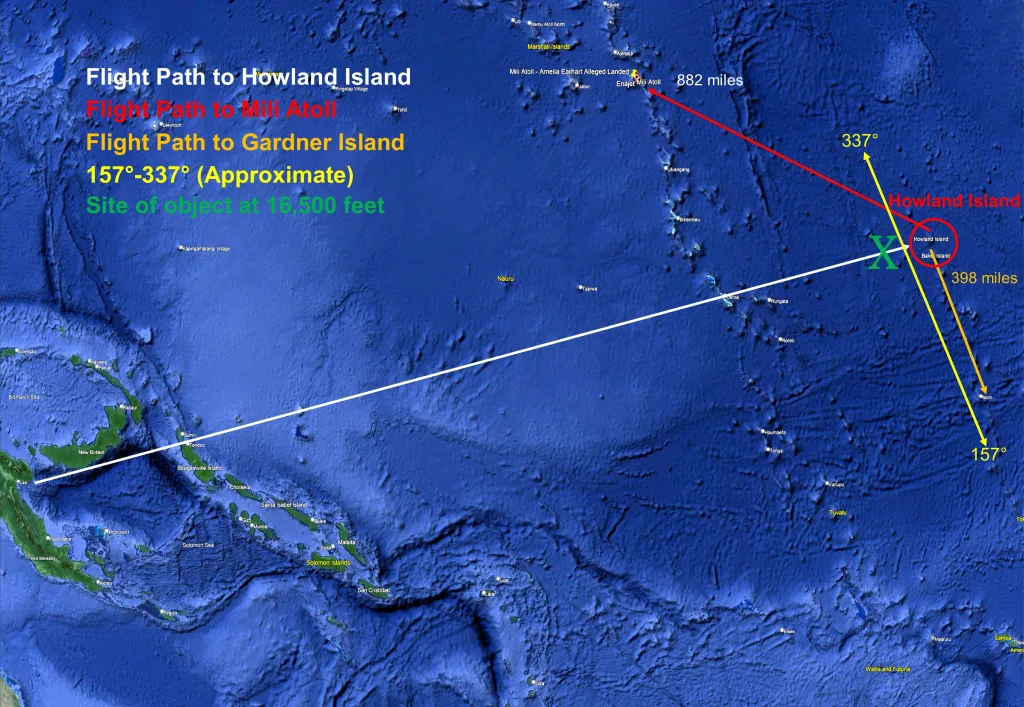

According to TIGHAR, The International Group for Historic Aircraft Recovery established in 1985, Amelia crashed on Gardner (now known as Nikumaroro) Island, approximately 398 miles south of Howland Island. Over the years, TIGHAR personnel made numerous expeditions to the island, and they believed artifacts found on the island confirmed their hypothesis that Amelia’s plane crashed on the reef surrounding the island. The tides caused the plane to slip into the ocean. TIGHAR compiled an impressive number of documents relating to the events leading up to her disappearance.

Over the years, numerous other theories arose. One was that Amelia turned north and flew towards the Marshal Islands, where she landed on the Mili Atoll, approximately 882 miles northwest of Howland Island. Amelia and Noonan were taken captive and killed by the Japanese who occupied the Marshal Islands at the time.

Another was that she simply ran out of fuel and crashed into the sea near Howland Island. A theory many experts support.

While proponents of the various theories advocated their opinions with alleged pieces of evidence, none that I found provided the “smoking gun” to prove their hypothesis.

What can also not be overlooked in evaluating the various theories are the mechanical difficulties that plagued the flight. They dealt with fuel consumption and navigation.

On June 8, in Dakar, West Africa, the plane’s fuel meter had to be repaired due to a broken shaft. Fuel flow meters were used to measure the engines’ consumption of fuel.

On June 15, there was a second issue with fuel control. This time, the manual mixture-control lever jammed during the hop from Assab to Karachi. Amelia could not regulate the amount of fuel used by the right engine, which she described as “gulping” large quantities of fuel.

On June 24, her pre-dawn takeoff at Bandoeng was delayed until mid-afternoon due to an instrument malfunction. During the flight to Saurabaya, she discovered the problem had not been fixed. Because of her navigational equipment malfunction, she returned to Bandoeng for repairs.

Had any of these malfunctions or a new one occurred over the Pacific Ocean, they could have spelled disaster. Over the vast Pacific Ocean, there were few places to land a plane. The solution to any problem would have hinged on fuel. How much fuel had been consumed?

In Last Flight, Amelia recorded that a base speed of 150 miles was used for all the flight calculations. The plane carried 1100 gallons of fuel. It would seem more than adequate, providing 22-26 hours of flight time, depending on which figure was used for the hourly rate of fuel consumption. By the time Amelia took off from Lae, she had flown her plane 22,000 miles in adverse weather conditions. She knew how much fuel the plane used. It was a detail that she recorded in several of her entries in Last Flight. She even described how the right engine gulped gasoline. Amelia didn’t have to guess. Yet, even Amelia was concerned about fuel consumption for the flight to Howland Island. Amelia sent her husband this telegram the day before she left Lae:

The Electra is poised for our longest hop, the 2,556 miles to Howland Island in mid-Pacific. The monoplane is weighted with gasoline and oil to capacity. However, a wind blowing the wrong way and threatening clouds conspired to keep her on the ground today. In addition, Fred Noonan has been unable, because of radio difficulties, to set his chronometers. Any lack of knowledge of their fastness and slowness would defeat the accuracy of celestial navigation. Howland is such a small spot in the Pacific that every aid to locating it must be available. Fred and I have worked very hard in the last two days repacking the plane and eliminating everything unessential. We have even discarded as much personal property as we can decently get along without and henceforth propose to travel lighter than ever before. All Fred has is a small tin case which he picked up in Africa. I noted it still rattles, so it cannot be packed very full.

https://www.thisdayinaviation.com/tag/territory-of-new-guinea/

Excerpt from a letter written by Harry Balfour, the Lae radio operator.

In everything I have read over months of research, I found these comments about items left behind the most compelling and telling of Amelia’s mindset. Why the necessity to remove such small items? These items would not have significantly increased the weight of the plane. Yet, she and Noonan repacked the plane, leaving non-essential items behind. There was only one reason, to conserve fuel, however, minimal the savings.

Another interesting detail is the reason for the delay. Amelia first planned to take off for Howland Island on June 30th. This was delayed due to adverse weather conditions over her flight path to the USS Ontario. On July 1st, the take-off was delayed because Fred could not set his chronometers, not because of his drinking problem as reported in several articles.

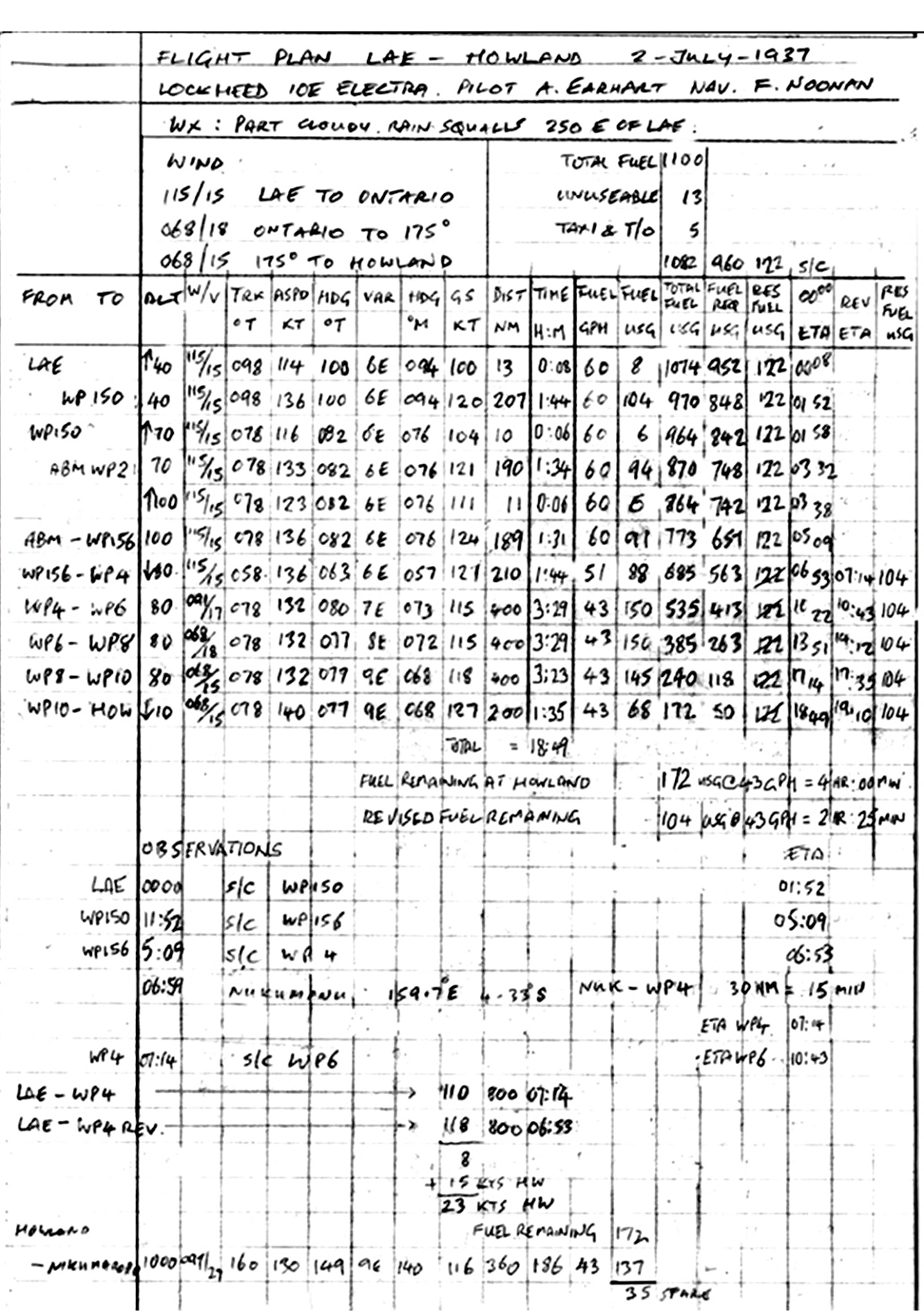

This flight plan was an intriguing find. The flight plan would have been left at Lae. In comparing the handwriting to Amelia and Noonan’s, there is a distinct similarity to Fred Noonan’s handwriting. It should also be noted that the miles, a total of 2130, are nautical miles.

The calculations were based on wind speeds (115/15, Lae to Ontario, 068/18 Ontario to 175°, and 068/15 175° to Howland) from the weather report Amelia received on July 1st with twelve to fifteen knots to Ontario and eighteen knots to Howland. It should also be noted that the weather report referenced a longitude of 175 degrees, which was added to the flight plan.

July 1st: From Fleet Air Base, Pearl Harbor

FOR EARHART FORECAST THURSDAY LAE TO ONTARIO PARTLY CLOUDY HEAVY RAIN SQUALLS 250 MILES EAST OF LAE WIND EAST SOUTH EAST TWELVE TO FIFTEEN PERIOD ONTARIO TO LONGITUDE ONE SEVEN FIVE PARTLY CLOUDY CUMULUS CLOUDS ABOUT TEN THOUSAND FEET MOSTLY UNLIMITED WIND EAST NORTHEAST EIGHTEEN PERIOD THENCE TO HOWLAND PARTLY CLOUDY SCATTERED HEAVY SHOWERS WINDS EAST NORTHEAST FIFTEEN PERIOD AVOID TOWERING CUMULUS AND SQUALLS BY DETOURS AS CENTERS FREQUENTLY DANGEROUS

In the July 2nd weather report, wind speed increased to twenty-five knots to the USS Ontario and twenty knots to Howland Island. Amelia never received this dramatic change before she took off nor received the updates transmitted by Balfour from the Lae radio station with the revised wind speed.

The total amount of fuel was 1100 gallons, with 13 gallons stipulated as unusable and 5 gallons for taxiing and takeoff. Once in the air, the plane had 1082 gallons of available fuel (Total Fuel USG), of which 960 gallons were designated as required fuel (Fuel Req USG) and 122 gallons as a reserve (Res Fuel USG). (960 +122 =1082)

By the end of the flight, in the column labeled Fuel Req USG, 50 gallons remained, bringing the fuel used to 910 gallons. (960-50) This is an average of 48 GPH (gallons per hour) for the eighteen-hour and forty-nine-minute flight.

The 50 gallons added to the 122 reserve gallons indicated the plane would still have 172 gallons of fuel when it landed on Howland. The 172 figure is also reflected in the column labeled (Total Fuel USG). Under this is written: Fuel remaining at Howland 172 USG @ 43GPH= 4 hr: 00 mn. The time was derived by dividing 172 by 43.

About midway on the flight plan, it was altered. The 122 gallons of reserve fuel dropped to 104 gallons. A statement was added: Revised fuel remaining 104 USG @ 43GPH=2hr:25mn. The only factor that changed was adding twenty-one minutes to the estimated time of arrival. The new ETA was now nineteen hours and ten minutes. While a twenty-one-minute increase wouldn’t seem significant, it used another 18 gallons of fuel. (122 gallons-104 gallons = 18 gallons). The corrected fuel usage was based on the 51 GPH figure. Deducting the fuel required for the extended ETA from the reserve column may have been easier than refiguring all the totals in the other columns. The mystery is what prompted the correction. Why did the ETA change?

The only problem is the total fuel remaining had changed to 154 gallons, not 172. (50 gallons + 104 gallons=154 gallons) One hundred and fifty-four gallons gave Amelia another three and one-half hours of flying time beyond the ETA of nineteen hours and ten minutes.

Based on Amelia’s last transmission, her flight time was twenty hours and thirteen minutes. The additional time of 63 minutes equates to 54 gallons of fuel. On paper, Amelia had 100 gallons left.

None of this considers the impact of the headwinds. For the last set of calculations on the flight plan, the 400 miles to Howland, the wind speed dropped to fifteen knots from eighteen on the previous 400 miles. The reduction of three knots of wind speed equated to 3:23 hours instead of 3:29 and 145 gallons instead of 150. That slight change with a lower wind speed saved five gallons of gas.

Considering the reverse, Amelia was bucking twenty to twenty-five knots of headwinds, not fifteen to eighteen. If a reduction of three knots saved five gallons of gas, what was the cost in fuel for an increase of up to ten knots? If the headwinds bumped the consumption rate near the 60 GPH range, it would have not taken long to use the remaining 100 gallons. It is possible that Amelia was flying on fumes, a wing, and a prayer.

Amelia told us: 0742: KHAQQ calling Itasca we must be on you but cannot see you but gas is running low been unable to reach you by radio we are flying at 1000 feet.

Based on numerous accounts, there is a consensus that Amelia simply didn’t have enough fuel left to reach Gardner Island or an atoll in the Marshal Islands.

Amelia had finally heard the Itasca. After hours of hearing nothing on the radio, she finally hears a signal. She had to know she was close to the Itasca. In her final transmissions, she’s still trying to get a bearing on the ship. Amelia was still providing information on her position. She even told the Itasca radio personnel she would repeat her message on another frequency, but then—there was nothing. The Itasca radio personnel never heard her voice again.

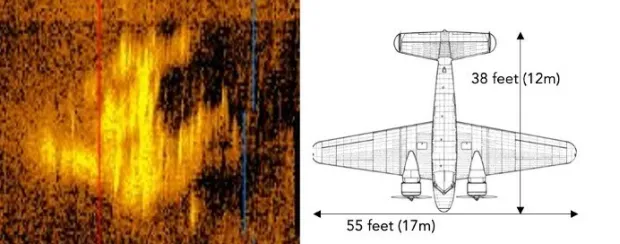

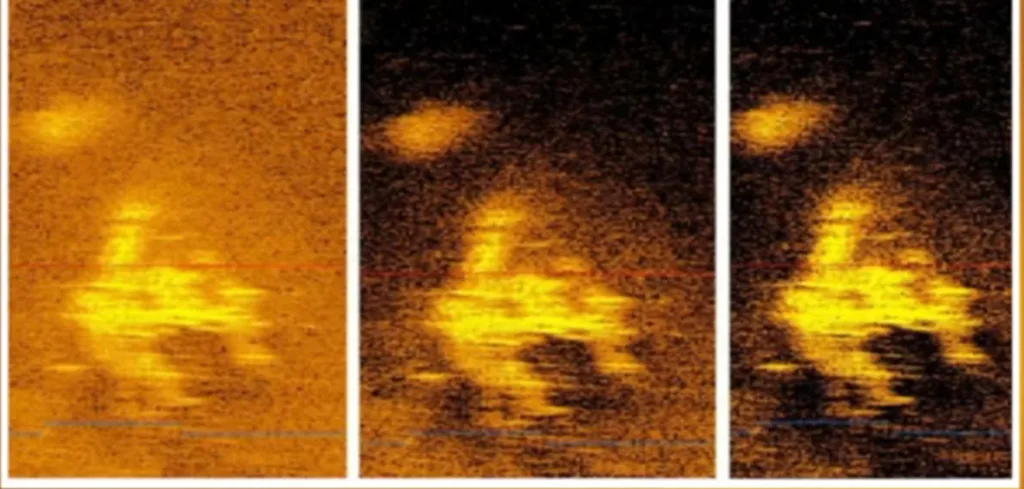

In January 2024, a startling headline hit the worldwide news network. Deep Sea Vision, an ocean exploration company, may have found Amelia Earhart’s plane. This image sparked a new interest in the disappearance of this iconic woman, who had dared so much. Had Amelia’s plane been found?

The company had been surveying more than 5,200 square miles of the ocean floor when their unmanned underwater drone captured an amazing sonar image about 100 miles west of Howland Island. The plane-shaped object could very well be Amelia Earhart’s plane. The image matches the dimensions of the Lockheed Electra 10E, even to the distinctive twin-tail. The object is around 16,400 below the surface of the water, which is deeper than the Titanic.

Amelia’s altitude, as reported to the Itasca, was 1000 feet. According to one account I read, from 1000 feet, the estimated impact was about a minute.

If this indeed is a plane, there are other intriguing questions. Is this the top of the plane, or the belly? The cockpit and engines are missing. If the plane is upside down, it could indicate the plane nose-dived, hitting the water headfirst and flipped over. The result would have been similar to a vehicle at a high rate of speed slamming into an object. The engine compartment disintegrates and the engine ends up in the passenger compartment, likely in the lap of the driver. The large image to the side of the main image could be an engine.

Is this the final chapter in Amelia Earhart’s Last Flight? At long last, has Amelia Earhart’s beloved “chariot” been found? The jury is still out. Deep Sea Vision plans on returning, this time to take pictures of the object. Will we have a conclusion, the epilogue to Last Flight, or will the haunting mystery continue?

Courage

Courage is the price that life exacts for granting peace.

The soul that knows it not, knows no release

From little things:

Knows not the livid loneliness of fear

Nor mountain heights, where bitter joy can hear

The sound of wings.

How can life grant us boon of living, compensateFor dull gray ugliness and pregnant hate

Unless we dare.

The soul’s dominion? Each time we make a choice, we pay

With courage to behold resistless day

And count it fair.—Amelia Earhart